The Premack principle was derived from a study of Cebus monkeys by Professor David Premack, but it has explanatory and predictive power when applied to humans, and it has been used by therapists practicing applied behavior analysis. Premack’s Principle suggests that if a person wants to perform a given activity, the person will perform a less desirable activity to get at the more desirable activity; that is, activities may themselves be reinforcers. An individual will be more motivated to perform a particular activity if he knows that he will partake in a more desirable activity as a consequence.

Stated objectively, if high-probability behaviors (more desirable behaviors) are made contingent upon lower-probability behaviors (less desirable behaviors), then the lower-probability behaviors are more likely to occur. More desirable behaviors are those that individuals spend more time doing if permitted; less desirable behaviors are those that individuals spend less time doing when free to act.

Just as “reward” was commonly used to alter behavior long before “reinforcement” was studied experimentally, the Premack principle has long been informally understood and used in a wide variety of circumstances. An example is a mother who says “You have to finish your vegetables (low frequency) before you can eat any ice cream (high frequency)”

Experimental Evidence

David Premack and his colleagues, and others, have conducted a number of experiments to test the effectiveness of the Premack principle in humans. One of the earliest studies was conducted with young children. Premack gave the children two response alternatives, eating candy or playing a pinball machine, and determined which of these behaviors was more probable for each child.

Some of the children preferred one activity, some the other. In the second phase of the experiment, the children were tested with one of two procedures. In one procedure, eating was the reinforcing response, and playing pinball served as the instrumental response; that is, the children had to play pinball in order to eat candy

Premack Principle Example

This is a principle of operant conditioning originally identified by David Premack in 1965. According to this principle, some behavior that happens reliably (or without interference by a researcher), can be used as a reinforcer for behavior that occurs less reliably.

For example, most children like to watch television–this is a behavior that happens reliably (they learn to like TV all on their own and it is something they will do willingly without any interference from their parents)–and parents often use this behavior to reinforce something children like to do less such as washing dishes. So, some parents might condition children to wash dishes by rewarding dishwashing with watching television. I’m not saying that is the right thing to do, only that it is an example of the Premack Principle.

Premack Principle ABA

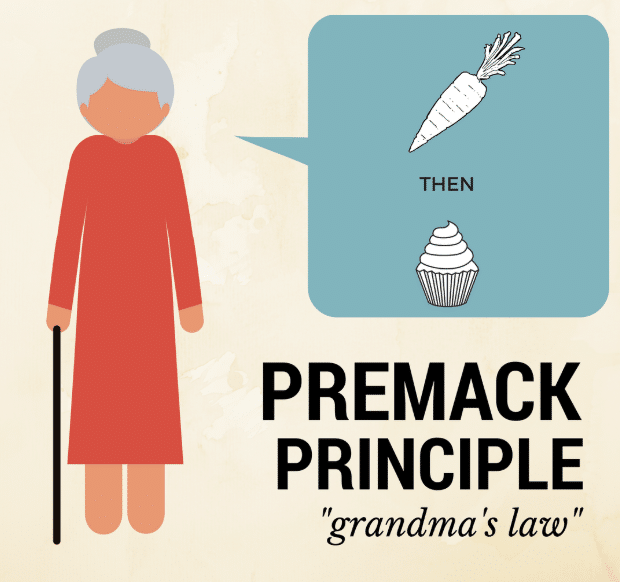

The Premack Principle is also known as “Grandma’s Law.” Parents (and Grandmas) use it naturally all the time. It is the principle that offering something that happens often in a free operant situation to be contingent upon something else that happens with low frequency. So, for example, “You can watch television after you have finished your homework.” Or, “You can have ice cream for dessert after you’ve eaten all your broccoli.”

In 1974, Timberlake and Allison came up with response-deprivation hypothesis. This gives us a model to predict whether access to one behavior (the contingent, awesome behavior) will be reinforcing for another behavior (the instrumental response, or the broccoli).

The idea is that restricting access to a behavior creates a deprivation for that more probable behavior (I want ice cream!) and acts as an establishing operation (EO), making the opportunity to engage in that behavior a reinforcement for the less probable behavior (Ugh, broccoli).

Premack Principle Psychology

Premack decided to provide for four various toys that monkeys can play with. Then, he noted how long they are going to spend time playing with it and limit their access on these toys. He offered them longer time of accessing on the toys they like best; however, this is when they played the toys that they play less frequently. Surely, they started on playing with less-liked to play with the most-liked and most desirable toys.

After trying it to animals, Premack also gave kids their set of behaviors. For the first part of the experiment, he allowed them of spending the time in playing pinball or eating candy. He then noted the activity that every child preferred.

The Second Phase

For phase two, he divided the group for two halves. At the first half, if the children are interested in eating candy, they they must first play with pinball. For another half, they must earn pinball by means of eating candy. The reactions of the kids mainly depend on the set and established preference. If the children played with pinball, their interest on candy has no certain effect on their behavior. On the other hand, if they consider candy as their first choice, they play and adapt pinball in getting the one they want. Despite any group or preference, this very same principle plays out.

Also known as the Premack Principle in Psychology, this is where people can freely do the things they want and engage on some behaviors, like eating chocolate and potato chops other than exercising. Many probable behaviors may be tried for less likely behaviors to be reinforced.